The page is continued from Pre-Contact Lakota.

Below constitutes a rough draft version of this particular history section. The heavily-upgraded textbook version will be available soon.

Pt. 1: Early 1700s: The Cultural Impact of The French Conquest of The Great Lakes &

The Introduction of Guns

While the Huron were being driven from their homes by the French looking to monopolize the lucrative Great Lakes fur trade— called the Beaver Wars or French-Iroquois Wars of the mid 1600s, they drifted first into Lakota country on the northern Mississippi.

Trading Furs w/ Frenchmen

The Lakota then drove them away; they then settled in separate groups throughout Wisconsin & also north of the Mississippi headwaters. The Lakota then drove them further north to the shores of the Straits of Mackinac. During this time, the Fox,— deeply concerned that European rifles were being traded to their archenemy, the Lakota— joined forces with the Haudenosaunee (“Iroquois” to the French) in order to disrupt that deadly flow of merchandise.

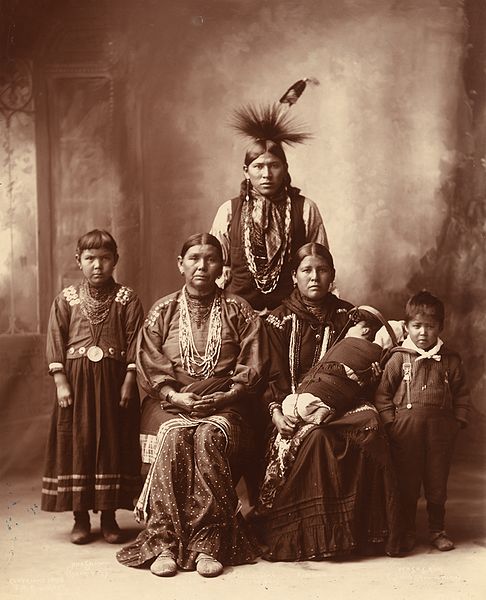

A Fox Family, 1899 A.D.:

As the bloodshed abated in the Upper Country, the governors of “New France” took advantage of the lull to consolidate their position. Ambassadors went out from Montreal, inviting all the tribes to gather for a mass celebration of friendship & peace. Then the day arrived: in midsummer of 1701 canoes began landing on the beach at Montreal-Sauk: Fox, Winnebago, Potawatomi, Miami, Huron, Anishinabe, Kickapoo & Lakota arrived in their eagle feathers & buffalo robes. In addition to these, French allied tribes came with their former enemies: the Five Nations of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy— Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, & Mohawk (this was prior to the “sixth nation” of the Confederacy, the Tuscarora tribe, being admitted into the league around 1720 A.D.)[1]. The Great Peace of Montreal (French: La Grande paix de Montréal) was a peace treaty between New France and 40 First Nations of North America. It was signed on August 4, 1701, by Louis-Hector de Callière, governor of New France, and 13 hundred representatives of 40 indigenous nations.[2]

Kondiaronk– Ceremony of the Treaty of the Great Peace of Montreal in 1701

Close to 1,300 people attended, representing 39 separate tribes, & together they feasted & parleyed & smoked the calumet (sacred pipe). The delegates worked out some last-minute details. The Iroquois received the right to hunt in Ontario country, & western tribes were given free access to trade in New York. But important issues remained unresolved. Far more difficult was the matter of the Fox. All through the peace negotiations the Fox protested bitterly that French traders were still supplying their Lakota enemies with guns. Already the arms deals had driven them into a secret alliance with the Iroquois.

Forced to play both sides in the high-stakes game of woodland power politics, the Fox did not take kindly to insult or neglect. French arms continued flowing to both the Lakota & the Anishinabe, & no matter how loudly the Fox objected, the French refused to listen. So, The Fox war parties began staging lightning raids on key French outposts, crippling trade in the Upper Country. Nothing was safe. Isolated villages, canoe portage routes— Fox raiders hit them all. The French unsuccessfully attacked them repeatedly, but the Fox knew how to live among their own lands better than the French did among these foreign ecosystems. The Fox then made peace with the Anishinabe in 1724, & allied themselves in 1727 with their former enemies the Lakota, thus ending hundreds of years of war between each other.[3]

Setting the Record Straight: “Sioux” is a French Slang Word

It’s a partial word― a slang word; “Sioux” comes from two words: “Nadowessi” comes from the Chippewa language― meaning “little serpent”, & “Oux” is the French way of pluralizing a word in order to denote “more than one”― the same way that in English we add the letter “s”. The Chippewaean word for “little serpent” was pluralized by the French into the word “Nadowessioux”, & then shortened into “Sioux”. Sioux has no meaning in the Chippewaean or French languages.

Nadowessi refers to the Ojibwa Nation; Nadowessioux refers to the Ojibwa Nation and the Dakota Tribes; Sioux refers to the Dakota Tribe. Later the US government lumped the Lakota and Nakota Tribes in this one word to cover them all: “Sioux”.

Lakota Oyate (“Lakota Nation”) is a proper name― not “Sioux Tribe”. Tatanka Oyate (Buffalo Nation) or Oceti Sakowin (Seven Council Fires) are proper names for the Seven Buffalo Nation Tribes of the Great Plains.[4] There are 3 major divisions based on language divisions within these tribes: Dakota, Lakota, & Nakota.

It is worth noting that the term “Indian” traces its etymological roots to the Old Persion word “Hindu”, or the Sanskrit word “Sindhu”, which denotes “people near the Indus River”.[5] This term was first misapplied to the indigenous peoples of the Americas following the expedition to the Americas by Christopher Columbus, who arrived on an island in the Bahamas archipelago, which he named San Salvador. Columbus was not the first European explorer to reach the Americas, however, having been preceded by Vikings led by Leif Erikson around 1000 A.D., who first arrived at Newfoundland & traveled beyond, but never really colonized like the French, English, or Spanish empires.[6]

Pt. 2: Mid to Late 1700s: The Cultural Impact of The Pueblo Revolution Against The Spanish

The Introduction of Domesticated Horses

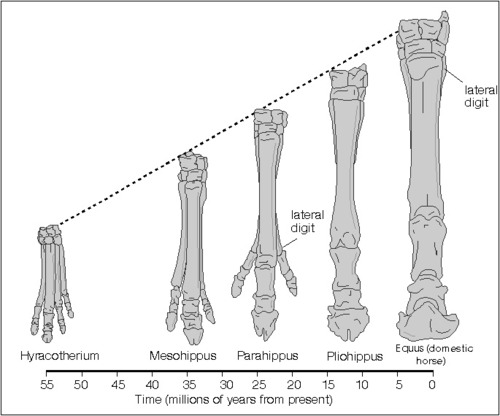

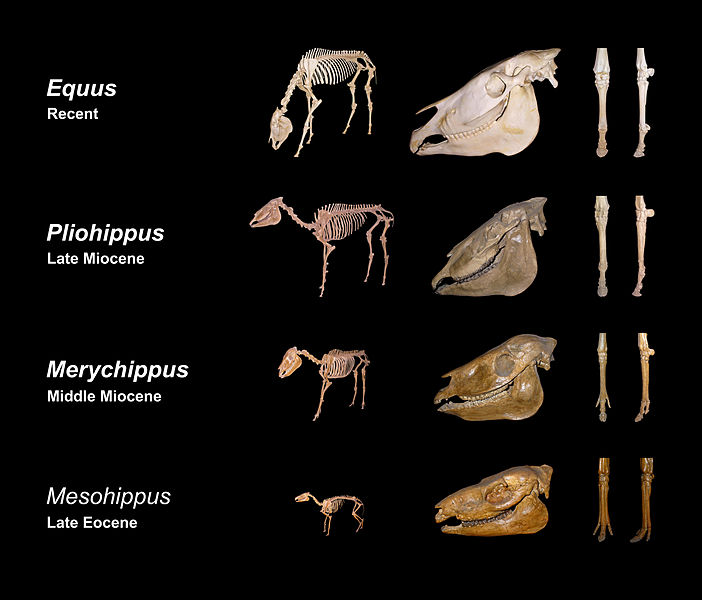

When Spanish explorers rode into the West in the 1540s, their horses were, in a sense, coming home. The horses they brought with them were originally native to the Great Plains, descendants of the collie-sized {hyracotherium} that appeared more than thirty million years ago. Most horses went extinct about ten thousand years ago at the end of the last ice age. Before that, however, some had crossed the exposed bridge of land that once connected today’s Alaska with Siberia, & as their cousins vanished in the Americas, they survived & flourished in central Asia, the largest grassland on earth.

Depiction of The Hyracotherium (based on fossil record):

Evolution of Feet to Hooves:

Evolution of Skull (not to scale):

Roughly five thousand years ago people on the vast pastures of Central Asia first domesticated horses, & the first empirical horse culture— was born. Life on horseback offered enormous advantages in trade, hunting, & especially warfare, & beginning with the peoples of central Asia, most horse cultures would turn to conquest, & most cultures who were conquered by them would in turn adopt the horse and such military culture: China, the Middle East, North Africa, & then Europe.

Mural depicting victory of General Zhang Yichao over the Tibetan Empire in 848 A.D.:

Birch Bark Plate from Silla Kingdom’s (57 B.C.- A.D. 935) “Cheonmachong“, the Tomb of the Heavenly Horse[7]:

One of the largest conquest-based horse cultures was that of the Spanish, who developed a strong equestrian military. After 1492, the equestrian-based Spanish empire turned to the conquest of the Caribbean, South America, Mexico, & then into the area now known as The United States.

“The Conquest of Mexico paintings“ (several shown below) are significant both artistically and historically. Painted in the seventeenth century, they detail the 1521 Spanish conquest of the native Aztec people.

“The Meeting of Cortés and Moctezuma”

“Don Hernán Cortés”

Portrait by José Cisneros:

Conquistador de Mexico – c. 1526, from University of Texas at El Paso: http://admin.utep.edu/default.aspx?tabid=62712

Conquistador de Mexico – c. 1526, from University of Texas at El Paso: http://admin.utep.edu/default.aspx?tabid=62712

“Arrival of Cortés in Vera Cruz”

Upon receiving word of Cortés’s arrival on the coast, Moctezuma, the leader of the Aztec empire, sends his ambassadors to meet the Spanish explorers. Cortés orders a show of military strength to impress the ambassadors:

“Death of Moctezuma”

“The Sad Night”

“The Capture of Tenochtitlán”

Cortés leads his Spanish armies on horseback across one of the causeways and lays siege to Tenochtitlán. He orders the complete destruction of the city.[8]

After conquering, enslaving, & desecrating the cities & traditional sites of many indigenous tribes of South America, from there conquistadors led columns of horsemen northward into present-day Arizona & New Mexico.

The Spanish Empire’s Conquest of The Pueblo, & Its Effect On The Great Plains Tribes

When the first Spanish explorers discovered the Pueblo Indians of present-day New Mexico, they found thriving tribes with rich cultures. The Pueblo people had come a long way from their hunting & gathering ancestors. They had learned the art of agriculture from indigenous peoples of Mexico centuries before, thus planting much of their own food. Hunting had also become an easier task with the introduction of the bow and arrow by the prehistoric Mogollon tribe centuries prior.

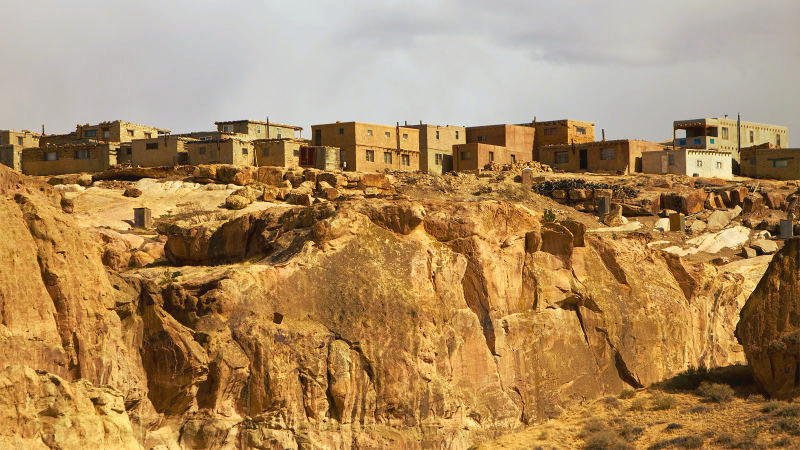

The Pueblo people made their homes from mud, forming it into any shape, building both one and two-story structures. They lived in small, tight-knit communities, sharing culture & sometimes language, but each pueblo remained independent. Because of their way of life, the Spanish named them ”Pueblo,” the Spanish word for “town”. The oldest continuously occupied village in North America is “Sky City” (just west of modern-day Albuquerque, New Mexico), built upon a 367-foot sandstone bluff, & first built around 1150 A.D.:

Upon the return of Fray Marcos de Niza, & his reports of cities of vast wealth to the north, in January 1540 Francisco Vázquez de “Coronado” was appointed leader of a major expedition to conquer the area north of “New Spain” (which is today modern day “Mexico”). Coronado quickly amassed soldiers & supplies, funded largely by Viceroy Mendoza and Coronado’s wife (Beatriz de Estrada)– as well as several others- all hoping for a return of jewels and precious metal. By February, a thousand men, and hundreds of horses, mules, cattle, sheep gathered at Compostela, west of Mexico City near the Pacific Coast, in preparation for the journey. The party included approximately 240 soldiers on horseback, 60 foot soldiers, & about 800 African and indigenous slaves.

A Depiction of Coronado’s Expedition:

(painting by Frederic Remington)

Fray de Niza traveled as the guide. Two ships, commanded by Hernando de Alarcón, would carry the bulk of supplies up the Guadalupe River. At last, the party reached the “Cibola” (cities of vast wealth) described by Fray. However, the adobe village was not city of gold. Upon approaching the site, Coronado knew that this settlement would not yield the wealth he was was told was there. However, he decided to conquer the Zuni pueblo anyway, & did so in 1540. Fray de Niza was ejected from the expedition for his gross exaggeration of the area’s wealth; he returned south in disgrace.[9]

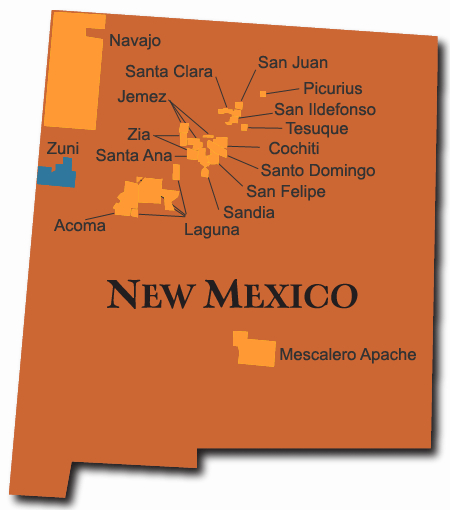

Map of Current Location of Zuni Pueblo, & Related Tribes:

A Second Expedition of Conquest:

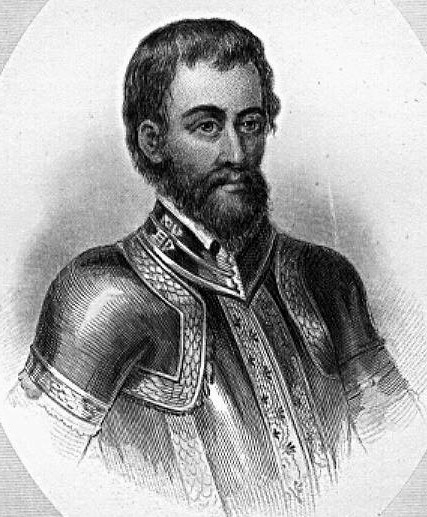

After being named second in command under Francisco Pizarro during the conquest of the Incan Empire (modern day Peru), in 1532, another conquistador (conqueror) named Hernando de Soto returned to Spain in 1536[10] with an enormous share of treasure from the Inca Empire. He was then admitted into the Catholic-owned Order of Santiago and “granted the authority to conquer Florida”.[11] Upon landing in 1539, de Soto and more than 700 Spaniards immediately began taking over native villages to use as camps. De Soto & the Spaniards proceeded to take advantage of the tribal people & selfishly squander their resources.[12] Soon they would come to capture Chief Tuskaloosa of the Mississippi tribe at his home village. Tuskaloosa advised the expedition to travel to a town known as Mabila (present day central Alabama), where supplies would be waiting for them. Upon arrival, the Spaniards knew something was amiss. The town of Mabila, as described by Garcilaso de la Vega as follows:

- “…on a very fine plain (with) an enclosure three estados (about 16.5 feet or 5-m) high, which was made of logs as thick as oxen. They were driven into the ground so close together that they touched one another. Other beams, longer & not so thick, were placed crosswise on the outside and inside and attached with split canes & strong cords. On top they were daubed with a great deal of mud packed down with long straw, which mixture filled all the cracks & open spaces between the logs and their fastenings in such manner that it really looked like a wall finished with a mason’s trowel. At intervals of fifty paces around this enclosure, were towers capable of holding seven or eight men who could fight in them. The lower part of the enclosure, to ‘the height of an estado’ (5.55 feet), was full of loopholes for shooting arrows at those on the outside. The pueblo (town, not tribe) had only two gates, one on the east & the other on the west. In the middle of the pueblo, was a spacious plaza around which were the largest and most important houses.“[13]

The population of the town was almost exclusively male- young warriors and men of status. There were several women, but no children. Also around the fortress, all trees, bushes, & even weeds had been cleared from outside the settlement for the length of a crossbow shot. Outside the palisade, in the field, an older warrior had been seen haranguing (military-style training, as a commanding officer would do) younger warriors, & leading them in mock skirmishes & military exercises.[14] The town of Mabila was a Trojan-horse, a fake village concealing over 2500 native warriors who knew of the conquistadors, & they were in waiting. There, Chief Tuskaloosa asked de Soto to allow him to remain there. When de Soto refused, Tuskaloosa warned him to leave the town, then withdrew to another room, & refused to talk further. A lesser chief was asked to intercede (intervene), but he would not. One of the Spaniards, according to Elvas, “(then) seized him by the cloak of marten-skins that he had on, drew it off over his head, and left it in his hands; whereupon, the Indians all beginning to rise, he gave him a stroke with a cutlass, that laid open his back, when they, with loud yells, came out of the houses, discharging their bows.“

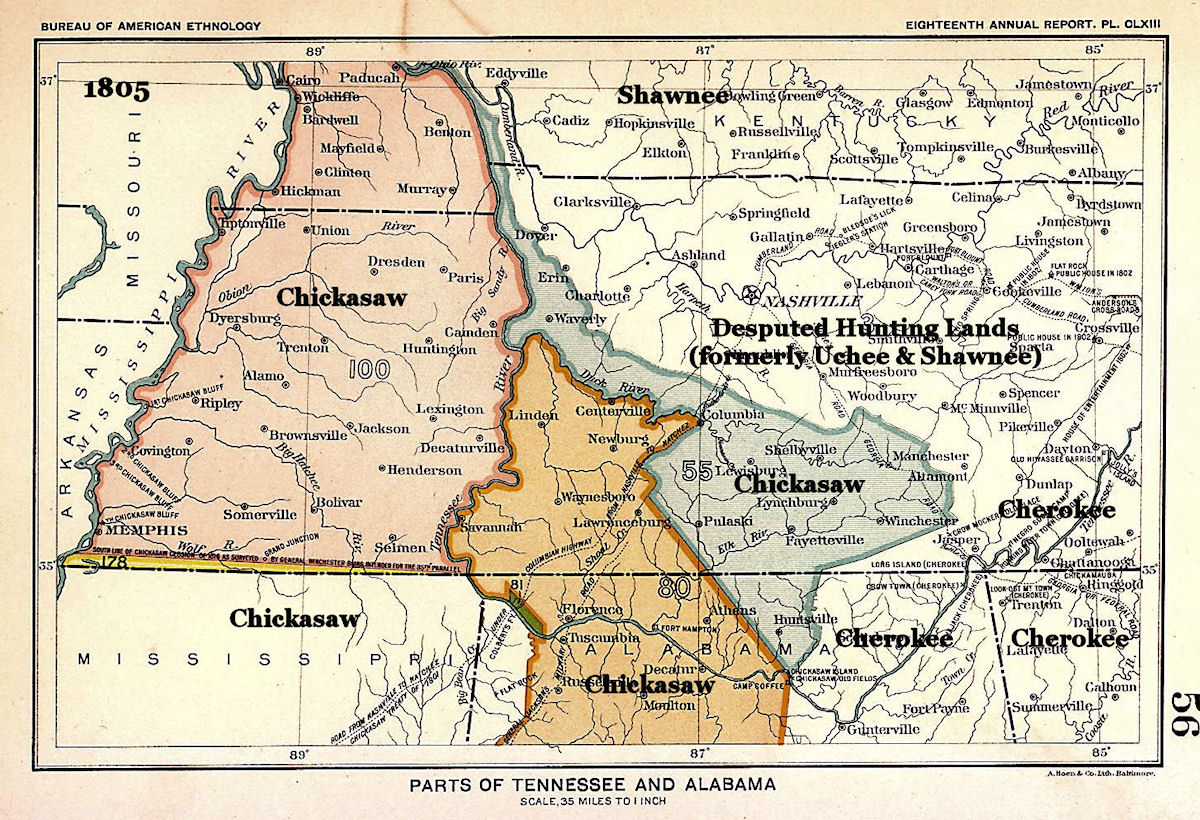

The Spaniards barely escaped the well-fortified town. The tribe closed the gates, and (Elvas continues) “beating their drums, they raised flags, with great shouting… fought (and) drove our people back out of the town,” then, de Soto & his people began “… breaking in upon the Indians and beating them down, (at which time, the natives) fled out of the place, the cavalry & infantry driving them back (into) the gates, where, losing the hope of escape, they fought valiantly; and the Christians getting among them with cutlasses, they found themselves met on all sides by their strokes, when many, dashing headlong into the flaming houses, were smothered, and, heaped one upon another, burned to death.” The greatest loss of soldiers by the Spaniards occurred during the battle at Mabila., as recorded: “They who perished there (Native Americans who were burned to death) were in all two thousand five hundred- a few more or less: of the Christians there fell- two hundred… Of the living, one hundred and fifty Christians had received seven hundred wounds…“[15] This tragic event took place in 1540. From there, in the following spring, de Soto‘s expedition would head north & closer to The Great Plains- & into traditional Chickasaw territory:

In December of 1540, de Soto‘s band of conquistador’s arrived in Chickasaw territory, & a reluctant relationship was formed between the two groups. However, as his reputation would suggest, de Soto began to assume unjustified authority over the Chickasaw which began to disrupt their way of life.

Soon, he began making harsh demands of the tribal leaders, & the Chickasaw began planning an ambush to oust their increasingly unwelcome visitors, an ambush that would come to disrupt his plans, & ultimately put an end to his expedition in America.[16]

Following “The Winter of Discontent”

Just before sunrise, March 4, 1541, about three hundred Chicasaw warriors, divided into many small groups, crept silently through the savannahs to encircle & infiltrate the sleeping Spanish encampment- which until ten weeks before had been a Chicasaw village. They were about to execute the attack that had been planned throughout winter, as warriors had been paying what had appeared to be social visits to the Spanish, but were actually reconnaissance missions, in which they noted everything about camp that could enhance their opportunity for a successful attack.

A Chickasaw Warrior

(sculpture by Enoch Kelly Haney is located at Bacone College campus in Muskogee, Oklahoma)

At that time there were an estimated four hundred fifty to five hundred men and two women operating under de Soto. Although he believed in the moral righteousness of abusing & killing non-Christians, he knew or suspected that despite their overtures of friendliness, the native people deeply resented his presence, & he sensed they were “engaged in evil intrigue.” Before he had retired on the evening of March 3, De Soto told his men: “Tonight is an Indian night. I will sleep armed and with my horse saddled.“[17]

Hernando de Soto:

The Spaniards lost about 40 men, & the remainder of their limited equipment. According to participating chroniclers, the expedition could have been destroyed at this point, but the Chickasaw let them go. Their village was utterly destroyed. The Spanish salvaged what little they could from the ashes of their camp, & de Soto ordered a move two or three miles away to another abandoned Chickasaw village on an open plain. There they tended to the wounded, & to rejuvenating themselves into a semblance of an expedition. Again, the chroniclers noted that had the Chickasaw attacked at this time, not a man would have survived. But, in keeping with the overall Chickasaw strategy of minimizing their own losses, they probably believed that the Spanish had been critically crippled & would have no choice but to move on. But- when they did not- the Chickasaw attacked again on March 15, again just before dawn.[18] This attack was not nearly as sophisticated as the first one. For one thing, De Soto’s sentries, soldiers, & cavalrymen were ready, & during the battle there were deaths & casualties on both sides.[19] For another, the Chickasaw probably had a very limited objective: to demonstrate emphatically to de Soto that he must leave their land. Within days, the do Soto’s expedition moved out for good, forever weakened and demoralized, according to Elvas. Now, instead of searching for gold and riches, they were trying to find a water route to the Gulf of Mexico and their best chance of escape. De Soto would not make it back, however; he died of some infectious disease near the banks of the Mississippi River in May 1542.[20]

Back in New Mexico, The Conquest of The Pueblo Expands:

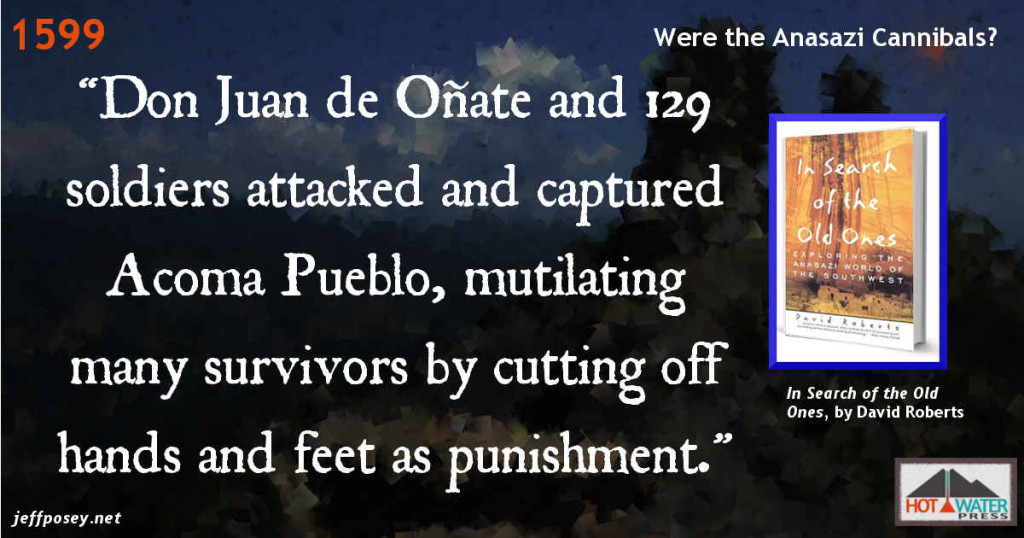

In 1595, conquistador Don Juan de Oñate was granted permission from (Roman Catholic) King Philip II to colonize Santa Fé de Nuevo México, present-day New Mexico.

Relations between the Spanish and the Acoma people had been mostly peaceful for several decades after the two groups first came into contact around 1540. However, in 1598, the Acoma leader, Zutacapan, learned that the Spanish intended to conquer them. Initially, the natives planned to defend themselves; however, their belief that the Spanish were immortal and their knowledge of Spanish atrocities committed in the past led them to try to negotiate a peaceful solution to the conflict. Accordingly, Don Oñate sent his nephew, Captain Juan de Zaldívar, to the pueblo to consult with Zutacapan. When Zaldivar arrived on December 4, 1598, one of the first things he did was to take sixteen of his men up the mesa on which the pueblo were located to demand food from them.[21] Even though the tribe chose to receive Oñate’s expedition in friendship. Historian Robert Silverberg says, even so, Juan de Oñate “claimed himself the master of domain” of Pueblo tribes “all the way to El Paso“.

On January 22, 1599, after the Acoma Pueblo revolted, killing 12 of their Spaniard overlords, the Spanish rulers retaliated by killing more than 800 Acoma civilians. To further subdue them, Oñate ordered a foot cut off every Pueblo male 25 years and over. Males between the ages of 12 and 25 were sentenced to 20 years of hard labor.

Spanish colonizers, mostly concentrated in the Rio Grande valley of New Mexico, knew their horses were the key to their control, & so they kept them, quite literally, on a tight rein. Only in 1680, when Pueblo natives collectively rose up & overwhelmed their Spanish overlords & drove them out of northern New Mexico for a dozen years (“Pueblo Revolt of 1680”), did the indigenous people of North America gain access to the Spanish herds. Once they did, horses & the Native American horse culture expanded at a breathtaking pace.

A crumbling church bell tower & wooden crosses mark the site of the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, Taos, New Mexico:

Spanish horses then became traded & stolen from one tribe to another. By 1700 the tribes of the Great Basin had them, & thirty years later those of the northern Rocky Mountains.

Map of the Great Basin:

By around 1780, a mere century after it had begun, the spread of the horse culture across the West was complete, & peoples from the Columbia River basin to the Great Plains were having their lives drastically reshaped. Once the people acquired the Spanish horse, in the mid 1700s, there was an impact on the material culture as well as the social customs of the people: tipis became larger, there was greater mobility, & hunting became more productive. Additionally, the horse had a direct impact on the integration of the warfare into the fabric of the people’s lives. It is important to understand the main object of Great Plains tribal warfare was never to acquire land or to control another group of people; instead if focused on raiding other tribes’ camps for horses, & acquiring honors connected with capturing horses. In these raids, very much like contests, men sought to out-smart the enemy & gain individual honors by “counting coup”, or striking the enemy with the hand or with a special staff or wand. Plains warfare emphasized out-smarting the enemy, not killing them. With the advent of the horse onto the Plains, warfare traditions became institutionalized among tribes.[23]

Over time, however, horses contributed also to native peoples’ mounting difficulties as the tide of white settlement rolled over them. The horse enabled tribal people to hunt far more effectively in many parts of the West, especially among the vast herds of bison on the Great Plains. Those bison were hunted for not only meat, but also their hides, which women processed into robes to feed a hungry market in the east and throughout Europe. Horses thus expanded Native trade & brought a flow of new items into their lives— a trade invigorated also because they could travel much farther & faster than before.

Horseback native people flexed their new power, & put it into play in the world around them. One result was a boom in population on western grasslands. Nearly all tribes that Europeans encountered on the Great Plains— Comanches, Lakotas, Cheyenne, Kiowas, Crows, Blackfeet, & others—migrated there during the era of horses, drawn by the new access to energy & power.

Some groups took fuller advantage than others, which resulted in a dramatic shifting of power across the West. With thousands of forbidding horseback warriors, Comanches created the largest empire in North American history, stretching from the central Great Plains deep into Mexico. Their fighting abilities on horseback soon earned them fearful respect throughout the southwest. In one of their earliest raids they stole a herd of over fifteen hundred. Their herds swelled to tens then hundreds of thousands. Soon no respectable chief would have less than a few thousand horses, & it wasn’t that uncommon for any warrior to own over a thousand.

Painting by Alfred Jacob Miller, of “a Sioux warrior demonstrating Comanche riding technique”:

The Lakota & Cheyenne dominated the northern Plains, & warred with the Blackfeet, Crows, & others over neighboring regions. On the Columbia Plateau, the Nez Perce used their huge horse herds to range over hundreds of miles, & to funnel trade from the Pacific coast to today’s North Dakota. For every winner, of course, there were losers. Village-dwelling groups like the Pawnees & Mandans on the Missouri River, & the Pueblos on the Rio Grande, suffered terrible raids from mounted enemies.

There were costs even for the winners. The quickening warfare over control of prime territories took an awful toll among warriors. By one census Cheyenne women outnumbered men three-to-two. The enormous herds needed to sustain a horse culture, numbering several animals for every man, woman, & child, soon had an alarmingly corrosive impact on streamside ecologies (“riparian zones”) where many native people had to spend their winters, leaving fewer & fewer sanctuaries during those desperate, storm-wracked months. Although other factors were involved, the prodigious hunting by horseback contributed to a dramatic decline in the number of bison, the animal essential for survival— especially on the Plains.

For all the calamities that came in the long run, European contact at first offered American Indian peoples many opportunities & advantages: Old World technologies provided a range of trade goods that brought vast improvements to everyday life: iron pots lasted virtually forever— compared to a fish hook whittled from bone, a metal hook seemed a miracle.

The enhanced connections to the wider world brought more than abundant goods. It likely was no coincidence that the first time smallpox swept across the West was in 1780, when the horse culture was in place & the virus could spread from people to people, from New Mexico to Puget Sound, during its short window of contagion. Even the vigorous flow of new goods had its downside. Native peoples’ growing reliance on metal goods, firearms, & other items they could not make for themselves left them increasingly vulnerable to the outsiders who supplied them, & more dependent upon trade & commerce to survive.

The far graver vulnerability was the partnership with the horse itself. The West, birthplace of the horse, in the end was the last place where the horse culture rose & flourished. Its reign was brief. After barely a century the westward roll of white society, with its irresistible numbers & its revolutionary technologies, including that of the railroad, undercut & overwhelmed the way of life that had brought unprecedented power, affluence, & glory to dozens of Indian peoples of the American West.[24]

The Plains Tribes in the late 1700s, Now with Horses and Guns:

Next Section:

[1]: The Six Nations Confederacy During the American Revolution, Compiled by Park Ranger William Sawyer: https://www.nps.gov/fost/learn/historyculture/the-six-nations-confederacy-during-the-american-revolution.htm

[2]: Francis, Daniel. Voices and Visions. Oxford University Press. p. 82.

[3]: An Introduction to Lakota Culture and History”: http://www.dream-catchers.org/lakota-history/

[4}: Lakota Country Times, “Sioux is not even a word” by Stacy Makes Good Ta Kola Cou Ota (Has Many Friends) Oglala Lakota Tatanka Oyate Stacy Makes Good Ta Kola Cou Ota (Has Many Friends) Oglala Lakota: http://www.lakotacountrytimes.com/news/2009-03-12/guest/021.html

[5]: Ancient History Encyclopedia: http://www.ancient.eu/article/203/

[6]: History – Leif Erikson (11th century)”. BBC: http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/erikson_leif.shtml

[7]: The Gyeongju National Museum, from “Gateway to korea”, article “Silla artifacts welcome museum-goers”: http://www.korea.net/NewsFocus/Culture/view?articleId=118280

[8]: Library of Congress, “Exploring the Early Americas, Conquest of Mexico Paintings”: https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/exploring-the-early-americas/conquest-of-mexico-paintings.html

[9]: The Arizona Experience, “The Coronado Expedition”: http://arizonaexperience.org/remember/coronado-expedition

[10]: Leon, P., 1998, The Discovery and Conquest of Peru, Chronicles of the New World Encounter, edited and translated by Cook and Cook, Durham: Duke University Press, ISBN 9780822321460

[11]: Leon, P., 1998, The Discovery and Conquest of Peru, Chronicles of the New World Encounter, edited and translated by Cook and Cook, Durham: Duke University Press, ISBN 9780822321460

[12]: The Chickasaw Nation, “First Encounter”: https://www.chickasaw.net/Our-Nation/Heritage/Heritage-Series/First-Encounter.aspx

[13]: Sylvia Flowers, “DeSoto’s Expedition”, U.S. National Park Service, 2007, webpage: NPS-DeSoto: https://www.nps.gov/archive/ocmu/DeSoto.htm

[14]: Charles Hudson (September 1998). Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun: Hernando de Soto and the South’s Ancient Chiefdoms. University of Georgia Press. pp. 234–238. ISBN 978-0-8203-2062-5. Retrieved March 3, 2012.

[15]: Sylvia Flowers, “DeSoto’s Expedition”, U.S. National Park Service, 2007, webpage: NPS-DeSoto: https://www.nps.gov/archive/ocmu/DeSoto.htm

[16]: The Chickasaw Nation, “First Encounter”: https://www.chickasaw.net/Our-Nation/Heritage/Heritage-Series/First-Encounter.aspx

[17]: Narratives of the career of Hernando De Soto in the Conquest of Florida, as told by a Knight of Elvas and in a relation by Luys Hernandez de Biedma, factor of the Expedition, Edward G. Bourne, editor, based on the diary of Rodrigo Ranjel, De Soto’s private secretary, (New York: Allerton Book Co., 1922), 133.

[18]: Mary Ann Wells, Native Land, (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi), 1994, page 23

[19]: Narratives of the career of Hernando De Soto in the Conquest of Florida, as told by a Knight of Elvas and in a relation by Luys Hernandez de Biedma, factor of the Expedition, Edward G. Bourne, editor, based on the diary of Rodrigo Ranjel, De Soto’s private secretary, (New York: Allerton Book Co., 1922), page 135.

[20]: Mary Ann Wells, Native Land, (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi), 1994, page 23 and David Duncan, Hernando De Soto, A Savage Quest in the Americas, (New York: Crown Publishers, 1995), page 400.

[21]: Knaut, Andrew. The Pueblo Revolt of 1680. Oklahoma: The University of Oklahoma Press: Norman, 1995, p. 69.

[22]: Research in United States Wars, “The Pueblo Rebellion (1680)”: http://www.uswars.net/pueblo-rebellion

[23]: Morison, Samuel (1974). The European Discovery of America: The Southern Voyages, 1492–1616. New York: Oxford University Press.

[24]: Official Portal for North Dakota State Government, The History & Culture of The Standing Rock Oyate: http://www.ndstudies.org/resources/IndianStudies/standingrock/migration.html